The most stressed-out man in Toronto

Just before the dawn of the Rob Ford crack scandal, Toronto's mayor was embroiled in a bitter effort to derail the "gravy train" and reign in spending at the City. I worked to capture the penny-pinching mood at City Hall in this profile of Mike Del Grande, Toronto councillor for Ward 39 and Toronto's city budget chief under Mayor Ford. As I discovered while writing this cover story, Del Grande had been given Toronto's most frustratingly thankless task.

His mission was to deliver on the Ford fiscal promise. But ever since he assumed the thankless task, controversial city budget chief Mike Del Grande has been, well, an unhappy camper. An inside look at the journey that brought him to the brink.

On a rainy Tuesday night in early December, a group of Toronto’s most fervent political junkies —public servants, bloggers, amateur policy wonks—gathered at the Annex’s Tranzac Club for an event called “WTF is up with the City of Toronto Budget?”

The event was the first in a new series organized by a volunteer group known as the #TOpoli Community. The goal is to demystify the inner workings of the city’s government, and that night, they started with the finances. It was an appropriate topic, given that the singular goal of Rob Ford’s administration has been to fundamentally change the way Toronto thinks about spending its money.

The beers were flowing, and the atmosphere was upbeat as Metro columnist Matt Elliott started the proceedings by using a colourful infographic to describe how City Hall balances its books each year.

Once Elliott completed his presentation, he made way for a panel that included journalist John Lorinc, civic participation activist Alejandra Bravo, and ParkdaleHigh Park councillor Gord Perks, a leftleaning voice in council and one of Ford’s most outspoken critics. Questions were tweeted in and read aloud, as the panel attempted to identify the best way the city should dole out its funds on a yearly basis. As one might expect, the discussion quickly morphed into a forum for the panelists to air a series of wideranging criticisms of Toronto’s famously taxaverse, service cutting powers that be.

Except that night, for once, Rob Ford wasn’t the primary subject of the group’s collective scorn. Perks introduced the crowd to a different culprit, who wasn’t even in the room. “The process is broken because the culture around budgeting is that we think we are so f—ed. Mike Del Grande says, ‘Where are we going to get the money?’ Listen Mike, being a bully is not how you make a budget! It’s f—ed. And I won’t have it!”

ScarboroughAgincourt councillor Mike Del Grande might not be a household name, but as the chair of Toronto’s budget committee, he’s an extremely significant figure at City Hall. If we view the Fords as the giant floating twin heads that lord over Toronto’s Emerald City, booming out threatening commands to all who dare set foot in their gravyless fiefdom, Del Grande is the man behind the curtain, breathlessly operating the city’s fiscal machinery.

Ask anyone at City Hall, and they’ll tell you the role of budget chief is without question the most stressful civic appointment. It comes with no extra salary, no extra staff, and very little of the limelight.

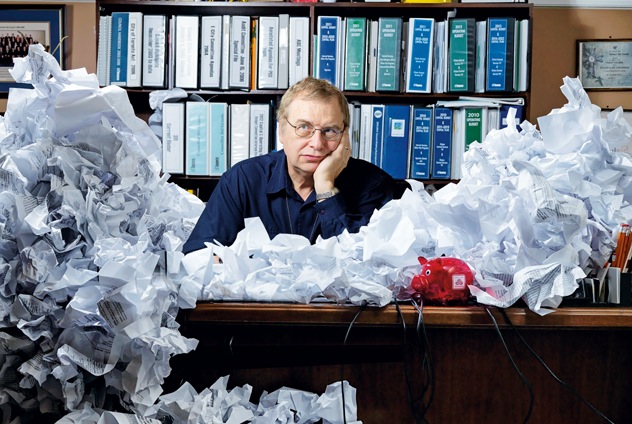

What it does come with is a giant heap of financial records. In Del Grande’s office, down at the end of a long hallway on City Hall’s second floor, you’ll find a neatly organized row of threering binders in cardboard boxes. They sit conspicuously on a bookshelf behind his desk, not far from his wall of diplomas, which includes a B.Comm, a CA designation, a master’s degree in theological studies, and a Bachelor of Education. There’s also some art on the wall: a depiction of Don Cherry and Ron MacLean in an American Gothic–style pose.

The first time I sit down with Del Grande to talk about the job, he’s seated at his desk, working away. With slightly tousled grey hair, a buttondown shirt with an open collar, and a facial expression that’s somewhere between bewildered and agitated, he conjures the look of a man caught in the middle of a perpetually confounding math problem.

It’s midNovember, the time when the annual budget process begins to heat up in earnest. Del Grande is preparing for the coming onslaught of budget committee meetings. Over the next few weeks, he’ll hear presentations from almost 50 city departments and agencies, among them Toronto Water, Solid Waste Management Services, and the Toronto Parking Authority. From there, Del Grande will preside over public deputations, oversee the repurposing of various funds, and get the budget committee and executive committee’s signoff on the 2013 financial plan before it hits council for debate on Jan. 15. And he’s repeatedly promised that if the budget doesn’t sail through council, he’ll resign.

You might think a fiscal conservative who suffered through the relatively freespending David Miller years would seem happier now that he has the opportunity to shape the city’s $9.4billion finances in his desired image. But the process, like the job itself, is painstakingly arduous, and it doesn’t take long to realize Del Grande isn’t a happy camper.

“I’m consumed by this job,” he says. “I come in here at 6 a.m., I don’t get home till 9:30. I’m doing Saturdays. I’m doing Sundays. I’ve given up going to the bathroom and eating. I’m just a workaholic trying to make things right.”

Within City Hall circles, Del Grande has become famous for his curmudgeonly manner. In person, he demonstrates why the reputation holds up—he speaks almost exclusively in these blunt tones.

David Soknacki, himself a former budget chief who spent three years as Del Grande’s conservative Scarborough colleague on city council, thinks the stern demeanour comes with the job. In his opinion, Del Grande demonstrates all the “warm cuddliness of an auditor.”

But Del Grande’s lack of social niceties isn’t what turned him—in the eyes of the left—into one of Ford Nation’s chief villains. At the heart of the matter lies Toronto’s nowfamed “revenue problem or spending problem” debate, an ideological divide that’s been raging in this city since the latter years of David Miller’s mayoralty. Mayor Ford and his allies bluster about what they perceive as outofcontrol spending at City Hall, while their adversaries claim city services could run more smoothly if the Ford administration weren’t so scared of taxes.

As we start to discuss the subject, Del Grande unleashes a deluge of complaints about Toronto’s purported issues with money management. Eventually, the cause of his angst rises to the surface: Every dollar is, to him, intensely personal.

“I grew up poor, so I know what it’s like to make a buck. My attitude is, any dime that’s spent out there, I treat it [like] it’s my own.”

Del Grande is so committed to efficient service that he occasionally leaves his office to drop in on city employees unannounced. If he catches them slacking off, there’s hell to pay. “I’m the kind of guy that will call them over, ask them if they know who I am. Most of the time they’ll say no. I tell them who I am, then they crap their pants,” he says. “And I basically just tell them, Look, the public wants to see value for their money. They’re working for me. I’m the boss. It’s my money.”

Del Grande’s ironfisted style of money management makes him a perfect fit for Rob Ford’s priorities, according to Myer Siemiatycki, a municipalpolitics professor at Ryerson University.

“There’s only so far any budget chief can stray from the agenda of the mayor,” he says. “Given how Mayor Ford has basically defined himself as a onenote mayor—namely, the friend of the taxpayer—that signals that the budget chief is not going to have a heck of a lot of autonomy and discretion. They’re going to go in a fiscally conservative direction, and in that regard, it’s a meeting of the minds between Mayor Ford and councillor Del Grande—that’s his own inclination as well. There’s been a onedimensional fixation on cutting back on expenditures.”

Indeed, Del Grande’s talking points are familiar to anyone who’s heard the mayor opine about respecting Toronto’s taxpayers. He decries City Hall’s fiscal discipline as “the worst I’ve ever seen.” Wasteful spending—those despicable “boondoggles”—drive him around the bend. Above all, Del Grande’s vision for Toronto is of a city that should use every last tax dollar wisely. And when it comes to encouraging city workers to pick up the pace, he’s startlingly candid.

“My philosophy? You don’t have to fire everybody. You take the biggest bull, the biggest problem, whatever the heck it is, and you gore it publicly. You make it bleed so bad that it scares the shit out of everybody else, to put them in line if things are going bad.”

A devout Catholic and a braintumour survivor, Del Grande set his sights on city politics after being restructured out of his job in the finance department of Shoppers Drug Mart in 2000. He finished his education degree at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education shortly before winning the council seat in his home ward of ScarboroughAgincourt in 2003.

Del Grande quickly became a prominent conservative voice at City Hall, first by criticizing the city’s budget under Miller, then by supporting Julian Fantino upon his ouster as chief of police in 2004. He also gained visibility on the right by being a Jane Pitfield booster during her 2006 mayoral run.

In the two years since Ford swept into power, the 59yearold has become one of the most trusted members of the mayor’s regime. So it’s strange to hear him say that if he’d had it his way, Ford never would have been elected mayor in the first place.

In 2010, Del Grande was gearing up for the race to replace the outgoing Miller by drumming up support for John Tory. When Tory opted out of running, Del Grande turned to his backup option —Rocco Rossi. But Rossi couldn’t pick up enough steam in the polls, leading Del Grande to the quarterchicken dinner that changed his life forever.

“[Rob Ford and I] met at a Swiss Chalet on Victoria Park between Sheppard and the 401,” he says. “He brought his brother along, and we had lunch.”

Though Del Grande says the choice to throw his support behind Ford was, in essence, making do with “the best of the worst [remaining candidates],” he’s responsible for doubling the number of Fords at City Hall: “It’s my fault—basically, I convinced [Doug Ford] to run. Rob didn’t really feel comfortable trusting anybody down here. I said to Doug, ‘Look, I think your brother needs you.’”

In exchange for his backing, the Fords offered Del Grande his choice of City Hall appointments, including deputy mayor and TTC chair. “I said, ‘The way the spending goes is the way the city goes, and we have a big problem with the spending. Miller wouldn’t let me near the budget— that’s the key spot. I’m almost compelled to do the job, because I’m the best qualified. You want me on that committee.’ So it wasn’t a deal, per se, it was just my offer. Reluctantly, [I said] I’ll take it on. It was with a whole lot of reluctance.”

Attempting to reset Toronto’s fiscal priorities has been draining, but the job exerts a toll on every councillor who dares take it on. Ward 33 councillor Shelley Carroll is one of Del Grande’s principal critics, but having served as budget chair for four years under Miller, she remembers the non stop stress. “It really is the worst and most thankless task you can take on council.”

She laughs heartily as she recalls how her perception of the city became distorted. “When it was snowing, they didn’t look like snowflakes to me. They looked like toonies. I’d send a [message] to the head of transportation saying, ‘Is this a $2million storm, or a $3million storm?’ And if it snowed all day and didn’t stop, at 5 o’clock I’m phoning saying, ‘Are you gonna [plow] the whole city again? Ahh! My god, it’s a $5 million storm!’”

With all the pressures that come with the job, perhaps it’s inevitable that every budget chief might occasionally see essential city services as massive piles of burning cash. But Del Grande seems to regard them as a nonstop fivealarm blaze.

When he discusses his budget strategy, he continuously repeats a few key catchphrases. “Good, prudent management” and “squirreling money away” are the ones that come up most often.

This nearobsessive focus on fiscal responsibility has earned him labels from the left like “penny pincher,” most notably for the hardline resistance he’s taken to increasing the city’s debt. For example, he continues to ignore repeated calls to take on greater debt to pay for capital investments like new streetcars.

This position is a source of extreme frustration for councillors like Carroll, who believe that the current recordlow interest rates make this a perfect time to invest in the city’s future.

“He’s not so much a bully as a singleminded person,” Carroll says. “He’s very singleminded about where he thinks we ought to go, which is nowhere.” She decries the central goal of this year’s budget: no increase in spending for Toronto’s city departments. “Zero growth. That’s their messaging. Why [are] we bragging about zero growth in a city that’s awash in cranes? You have to spend in a city like this—you don’t get a great city for free. The idea that the catchphrase for our budget should be ‘Zero’ is kind of scary.”

In midDecember, Del Grande patiently listened to two days of public deputations concerning the 2013 budget. Given three minutes each to speak before the committee, 117 citizens shared their views on the importance of services like children’s recreation services, shelter support and housing, and lawn bowling clubs.

For effect, Del Grande kept a running tally of the cost of these requests on a large chart beside his seat at the front of the room. The grand total: $817 million. The chart was a stunt, to be sure, designed to reinforce the notion that there are financial limits—that you can’t always get what you want. He believes that people heard the message.

“If I sat here and I was a goody twoshoes, I would be walked all over,” he says. “It would be a joke. So I’ve got to play the role: be firm, be fair, be questioning.” He hammers home each point by rapping his hand on the table, rhythmically reinforcing the resolve it takes to spend every day of your working life saying no.

But in addition to his call for costcutting measures, Del Grande believes he’s also demonstrated a willingness to compromise. He has repeatedly criticized Ford’s stated desire to eliminate the Land Transfer Tax, which brings in over $300million per year. In December, Del Grande agreed to dedicate money to hotbutton items like children’s nutrition programs, the Toronto Botanical Gardens, and cityrun community centres in priority neighbourhoods. Faced with the crumbling Gardiner Expressway, the new budget calls for $505 million in repairs.

Asked to help execute the mayor’s most significant campaign promises (namely, derailing the mythical gravy train and finding ways to cut), Del Grande has been ruthlessly efficient. This year, he successfully ushered in a balanced budget that didn’t rely on previous surpluses. The mayor publicly lauded this accomplishment, saying, “Del Grande took this bull by the horns and he wrestled it to the ground.”

Despite that kind of mayoral praise, Del Grande has repeatedly threatened to abandon his post. He says the original agreement struck at Swiss Chalet was for a twoyear stint, and he told reporters in December that his resignation as budget chief would be “guaranteed” if his fellow councillors dared to tinker with the 2013 budget plan, which was given to council on Jan. 15. Del Grande stressed that another surprise omnibus bill (like the one sprung on him last year, which undid $19 million worth of cuts to restore a number of city services, including youth programs, ice rinks, and WheelTrans for dialysis patients) would mark the end of what he calls his “personal sacrifice.”

“If they do that [again], I’m outta here. I’m not gonna give up family holidays, vacations, and everything else. For what?”

A job that’s all about poring over tiny details and obsessing over the bottom line leaves little time to consider the big picture. When asked to evaluate where he’d like to see the city increase its investments, Del Grande seems to have trouble even entertaining that possibility.

“There’s not enough money. There’s $817 million worth of demands. You want to make sure you have a safe city. You want to have a city with opportunities. For me, the endall and beall is jobs. Jobs for young people,” he says, suggesting that decreased taxes help keep businesses afloat. “The first time I got laid off in my young career, it was devastating. I’ve felt that. So that’s the biggest goal—not having lost generations.”

In a city so vast, with such a varied population, the choices made with respect to taxing and spending become an exceedingly delicate balancing act. Del Grande insists on frugality, truly believing that his plan will guarantee our city the best possible future. In the face of much vocal opposition, both from the media and many of his opponents on council, he forges ahead.

As our second interview draws to a close, I ask Del Grande what he thinks his legacy at City Hall might be. “I don’t think anyone will care, or even remember. Around here, good stuff is forgotten real quick. It’s the bad stuff that’s not forgotten. They caricature you. They say, ‘Oh, that guy’s Oscar the Grouch.’ That’s all they remember. Nothing about good stuff, nothing about compassion. Nothing.”

With that, he retreats. Back into the room stacked high with binders. Back to work.

In City Hall’s council chamber on Wednesday morning, speaking in advance of the budget vote, Del Grande is characteristically defensive. “I did my job,” he says. “I was vilified in many quarters.” Referring to the various motions—some 30 papers—that would add spending to the budget, he pronounces himself “distressed.” “I did what I needed to do,” he tells council. “You now need to do what you need to do.”

It’s not an explicit resignation, though it launches immediate speculation across social media that it will be Del Grande’s final speech as budget chief. And when council decides that what they need to do is add $12 million in new spending to the city budget, those rumours only grow louder. The mayor even proceeds to throw his support behind a successful motion for $3.1 million in extra funding to Toronto’s fire service; the day before, he had voted against his own proposed two per cent propertytax hike, preferring Giorgio Mammoliti’s zeropercent increase.

An hour after his speech before council, Del Grande turns to the reporters. The budget vote, he agrees, was “not a vote of confidence [in me],” but he declines to make good on his threat of resignation, saying only that he will speak with both the mayor and the city manager before any announcement about his post. The scrum lasts less than 30 seconds.

Twenty minutes later, the mayor calls the budget a “remarkable accomplishment”— he insists that they are changing the culture at city hall, that Toronto’s financial future is secure, that the budget chief is “a fantastic asset to our team.” Ford is flanked by his brother, by the deputy mayor, by a crowd of sympathetic councillors. Del Grande is not there.